Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle

Anarachism and Class Conflict in the Fin de Siècle

French socialism in the most general sense was more a matter of sensibility than of doctrine, partly because the country knew not one socialist doctrine but many. A united socialist or labor movement did not exist before the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1880s, the most forceful and visible section of the extreme Left was also the least organized: anarchism. Where socialists wanted to capture the state on behalf of the oppressed, anarchists sought not the capture of the state, but its abolition. True anarchists in a revolution, explained Jean Grave, one of their ideologues, should not stupidly proclaim a new government but shoot whoever tries to set one up. This sensible appreciation of how easily reformers turn into oppressors went along with distrust of all instruments of repression (army, police, bureaucracy, church, and schools), of private property, and of capital -- which could result only from the appropriation and accumulation of the value created by the work of others, that is, from theft. Most visibly, though, the anarchists were activists. Rejecting the patient preparation of revolution, let alone of elections and reforms by legal means, they argued that insurrectionist deeds were the most effective propaganda. Whatever its effectiveness, propaganda by deed evoked the sympathies of many and the attention of all.

Convinced anarchists were few, and during most of the 1880s their propaganda remained on the verbal level.27 Because they criticized property, the police, and military service, sometimes in inflammatory terms, anarchists often appeared in court charged with advocating murder, arson, pillage, or desertion. None of this, however, aroused much interest until the bombs began to explode in a vicious crescendo of repression and revenge. May 1, 1891, had seen anarchist riots in Paris; those arrested had been roughed up by the police before being tried and sent to jail. In 1892 the homes of legal officials involved in that trial began to be blown up; and Paris lived in terror until the author of the explosions was denounced by a waiter before whom he had disparaged the government ("What do you care who governs you?") and the army ("a lot of idlers").28

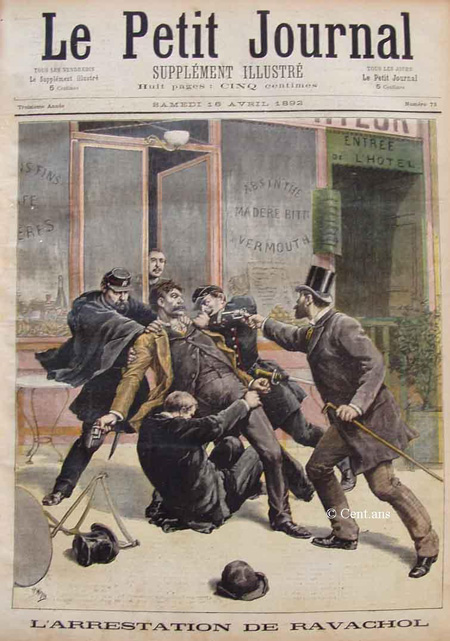

François-Claudius Koeningstein, a thirty-three-year-old dye worker, smuggler, and counterfeiter, who called himself Ravachol, declared that he had wanted to "terrorize in order to call attention to us, the true defenders of the oppressed." As he went on trial in Paris, in April

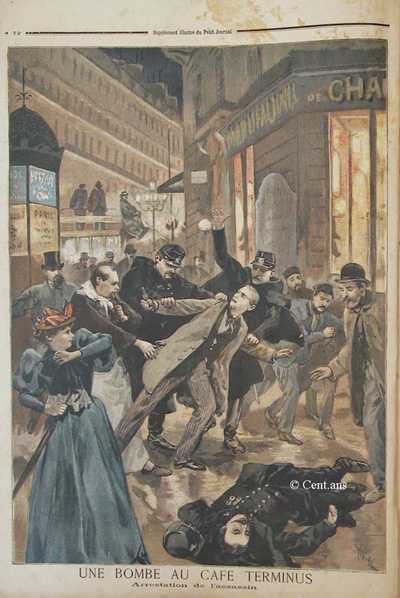

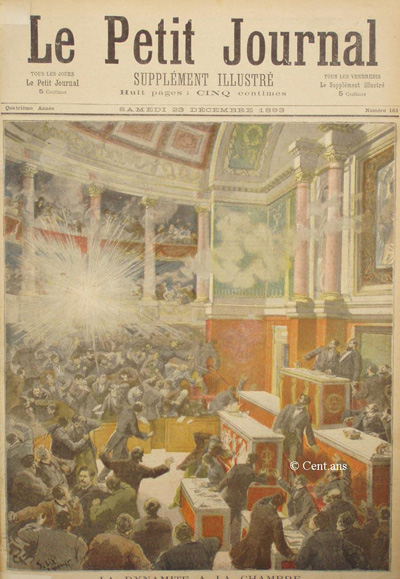

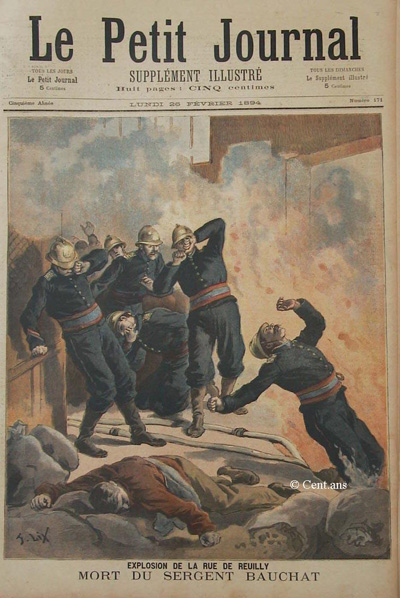

1892, a violent explosion in the restaurant where he had been arrested blew off the owner's legs and wounded a great many others. Condemned to hard labor for life for the bombings, Ravachol was then tried again at Saint-Etienne for five murders, a series of thefts, and a grave-robbery committed, as he explained, for the good of the cause; he was sentenced to death for the murder of an old man.29 Shortly after his execution another bomb exploded, this time in the Chamber of Deputies (December 1893), wounding several legislators. Auguste Vaillant, the twenty-two-year-old leather worker who had thrown it, was tried in January 1894. He explained in court that in his view neither crime nor criminals existed, everything being attributable to the milieu and the [dis]organization of society. A society as rotten and unjust as the present one had to be changed by any and every means. On February 2 Vaillant was executed; on February 16 Emile Henry, son of a Communard, threw a bomb into the Terminus Café, killing two and wounding more. The Terminus, at the Gare Saint Lazare, was not frequented by many exploiters of the people, but by a lot of their lackeys. As Henry explained, not just the bourgeois had to be punished, but all those who accepted the existing order, especially those small employees "who hate the people even more than the bourgeois do . . . the pretentious and stupid clientele of the Terminus."30

Condemned to die in April , Henry was executed in May 1894, while bombs were going off, it seemed, in hotels and restaurants throughout Paris. Fear turned folk back to religion: "We've never sold as much fish as this last Easter Week." On June 24, in Lyons, a twenty-one-year-old Italian, Santo Caserio, shouting "Vive Ia Révolution! Vive l'Anarchie!" stabbed President Carnot to death with a six-inch knife. Carnot had refused to pardon Ravachol, Vaillant, and Henry; now Caserio too would die, unpardoned, two months after his prey, last victim of this two-year frenzy.31

Would the murderous spiral have stopped without the lois scélérates,the villainous laws, passed after Carnot's murder? They made advocating anarchism an offense, ruled that anarchist trials could no longer be held before a jury, and removed all possibility of propaganda, including press reports. Caserio, we are told, was interested only in the statement that he planned to make in court, as his predecessors had done, evoking the admiration of men as eminent as the geographer Elysée Reclus. The new law prohibited the publication of his words, and let him die without an echo. One notes that the Radicals who condemned the lois scélérates in the harshest terms, maintained them when their turn came to govern the country.

Was it the repressive laws and their execution that discouraged further bombings, or a waning of public sympathy? In February 1894, as the Seine Assizes tried an anarchist who had murdered a policeman, the press found reason to comment that the public was growing tired of such affairs.32 For one thing, trial evidence made it fairly clear that the terrorists were trying to work out their personal problems even more than those of society. Ravachol was a professional criminal; Vaillant an unmistakable ne'er-do-well who changed women as easily as jobs. The twenty-year-old cobbler Léon-Jules Léauthier, condemned to life at forced labor for trying to murder the Serbian Minister in Paris with a shoemaker's knife, blamed the social organization that pre vented him from consuming according to his needs; it turned out that he never lacked work but never delivered it on time or did slipshod and ill-finished work.33

More ominous, out-and-out rogues were adopting the language of principle to justify their crimes. One of the first to do this, in 1887, was Clément Duval, who robbed the apartment of a woman painter (Proust's friend Madeleine Lemaire), set fire to it to cover his traces, then stabbed to death a policeman who tried to arrest him. Duval proclaimed "the right of those who have nothing to take from those who have" and described his arson as the act of "a convict setting fire to his jail." As for his encounter with the policeman: "He arrested me in the name of the law; I struck him in the name of liberty." It turned out that one of Duval's fences, who was a member of the anarchist group "The Disinherited of Clichy," enjoyed an annual income of 1,600 francs from stocks and bonds.34 The trial records of the late 1880s and early 1890s abound in thieves and murderers claiming the right to repossess the property of others, by force if need be. One of the more appealing among these was a member of an anarchist gang caught expropriating one more bourgeois after a long series of robberies and break-ins. "Your name?" asked the judge. "I am the son of Nature."35

With hindsight we can see that the First World War brought down the frames of institutions, ways of life and mind, that had been long crumbling. But there was no knowing this before the nineteenth century ended, before the twentieth century faced the possibility of a worldwide war. After that war was over it became fashionable to refer to the years preceding it as the Belle Epoque, and to confuse that period with the fin de siècle, as if the two were one. Perhaps they were; the bad old times are always somebody's Belle Epoque. But the Belle Epoque, named when looking back across the corpses and the ruins, stands for the ten years or so before 1914. These also had their problems, but relatively they were robust years, sanguine and productive. The fin de siècle had preceded them: a time of economic and moral depression, a great deal less redolent of buoyancy or hope.

And yet a lot took place during these two decades that made life better for a lot of people. Not for all. Better alternatives for the many easily turn into less choice for the few. New aspirations can be perceived as threats, especially when the aspiring begin to raise their voices. Transitions can be diversely recognized: as promise, or as menace. Different social groups see the same phenomenon differently. Even beneficent changes can be troubling: access to better food may stir regrets for the old, rough familiar fare; telephones invade privacy; swifter, cheaper transport frightens and pollutes; shorter working hours forecast idleness. Coarse sensualists welcomed the time of modern comforts succeeding "to periods of force and magnificence," delighted to think that it would go down in history as "the century of water closets, bathrooms, and central heating."1 Sterner observers deplored the softness and the laxness that the new facilities evoked. Coming too thick and fast upon one another, such impressions could be taken for evidence of present corruption, or omens of imminent decay. That is how some of the most articulate among contemporaries perceived and presented them, in the lurid context of military defeat, political instability, private adversity, public scandal, and clamorous social criticism, to stress the fin in fin de siècle that made it sound like an unhappy end.

This is what caught my eye about the circumstances: the discrepancy between material progress and spiritual dejection reminded me of our own times. So much was going right, even in France, as the nineteenth century ended; so much was being said to make one think that all was going wrong. That need not be surprising. Public discourse turns mostly about public matters--especially politics; and the style of politics calls for catastrophic imagery. A great deal of political debate either takes place on the brink of doom or envisions it looming on the horizon. Doom loomed more clearly in fin de siècle France than almost anywhere else at the time. Since contemporary interpreters and later historians pay special attention to politics, this colors their impression and ours of years when, as in most times, politics played only a small role on the surface of events. As one shrewd observer of his country put it, "politics does not hold in our lives the place it takes up in the newspapers, in [social] conversations, in the apparent existence of a nation. The public life of a people is a very small thing compared to its private life."2

Let me say at once that public life is far from irrelevant, because decisions made at the public level can powerfully affect the private one. Political ideas, though, remained the passion or plaything of small elites, until cheap print and popular illustrations extended them to all. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century political interests and ideologies came to stimulate the general public--more general than it had ever been--pervading popular attitudes and expectations, hence the eventual orientation of the land itself.

The harsh realities of universal suffrage, long eluded, were coming home to roost: lower and lower sections of the middle classes were ruling in parliament; setting the pace in society, letters, arts; tarring politics, so long a sport for gentlemen, with their vulgar brush. The populace, losing respect for their natural betters, bayed for its turn at the troughs of power. The disorderly, volcanic nature of city mobs was nothing new. The claims of organized labor, its disruptive strikes, the politics of socialism in Chamber, Senate, even the Cabinet, were more disquieting. The deferential society tottered. There was no knowing how long it would take to wane.

"A Bomb at the Cafe Terminus," Petit Journal, 1894

"Arrest of Ravachol," Petit Journal, 1892

Dynamite in the Chamber, Petit Journal (1893)

Explosion in the Rue de Reuilly, Petit Journal (1894)